An even bigger spark towards this revolution was his next film, "Psycho" which broke several norms. One of the most notable break from tradition was to kill off the lead lady in the first twenty minutes. That was unheard of. While in America, this was more or less ignored, the Europeans really used this material for inspiration, which would in turn come back to the Americans with the next generation in late 60s. This deconstructionist attitude was adopted first by Francois Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, and the rest of the French New Wave. They lauded Hitchcock's brave innovation and complete control over the authorship of his films. This is where auteur theory comes from - Truffaut's treatise on Hitchcock.

An important feature of the French New Wave was how self aware it was. In America, since about 1915, it was just the norm that the films had to maintain a certain illusion, and that any trace of creative force behind the action was to be completely hidden. The French were some of the first in a very long time to unapologetically make sure the audience was clear that what they were seeing was a careful fabrication of the director and that he was the puppet master in this drama that was unfolding. In a sense, that was the function of the director as auteur. This was the revolution: Self aware films, with an unmistakable DNA print of the director. It was such a power move.

It did not take long for this revolution to make its way to Sweden, where director Ingmar Bergman had made a pretty big name for himself for making some of the nation's most beloved comedies and dramas. Some major hits were "Wild Strawberries", "Summer with Monika", and "The Seventh Seal." He had a troupe of actors who were frequent collaborators such as Liv Ullman, Harriet Anderson, and Gunnar Bjornstrand. He had several personal ups and downs with his career and often times found himself unhappy with the direction of his work, and would become very depressed because of it. But it was always in these moments when he would come back, guns blazing, with something new and exciting. For instance, the first time this happened was in 1955, when he directed the comedy "Smiles of a Summer Night" after a few disappointing outputs of mundane dramas and films that were considered too artsy and "out there" for an audience. By around 1959, he had found himself in a similar situation. Being in a very bad place, he isolated himself for a time and then started work on an incredibly personal, yet ambitious trilogy about God and faith. The first film in this trilogy was "Through A Glass Darkly" which any routine reader of the Bible will recognize from 1 Corinthians 13: 11-13. The passage refers to Paul (in being a model for the spiritually immature and hedonistic Corinthians) putting away his childishness of youth and becoming a man and facing the uncertainty of adult life. But he concludes that even though we can only see through an obscured mirror at the fullness of truth, one day everything will be made known. But he sums this up by commanding the Corinthians to abide themselves into three things: Faith, hope, and love... at which Paul says that greatest of these is love. And therefore that becomes the thesis of Bergman's film, that God is love. There was a problem, however. In the middle of shooting, Bergman had a terrible crisis of faith and came out a reluctant atheist on the other side. So what was originally meant to be a beautiful treatise about finding hope and faith through love, kind of turned into a bittersweet uneasiness about God's existence. His followup, "Winter Light" took this even further and had an unsuccessful pastor give up on faith and declare that "God is silent because God does not exist." And then the third film, "The Silence" was a completely secularized experience and presented a world without a God, a world that Bergman felt that he was living in.

So after going through this tumultuous journey about trying to answer the question of whether God exists or not, the next logical step for him was to explore another unknown facet of life for him - that of the female experience. This was completely unheard of before, and even if a man did make a film about this subject, it was usually sexualized, exploitative, and/ or pornographic. Alas with his magnum opus "Persona", he does none of these things. There is frank discussion of female sexuality, but it was done so in a manner that affirmed female sexuality as real on its own right, and not merely something that had to be activated by a male dominance. In essence, Bergman made one of the first "feminist" films. It explores psychosis, abortion, femininity, and unapologetic female sexuality in one of the most sexually explicit dialogue scenes ever. Topics that are taboo even to this day where spotlighted in this film for possibly the first time on a commercial level. The American film industry had not yet become this relaxed and the fascistic Hays-Code was still very much in influence. But that was all about to change with this film. Paul Schrader remarked on the special features for the Criterion release of Persona, that every aspiring film student in the 60s studied Bergman extensively. And when you think of the guys who were in school at this time, namely Scorsese and De Palma, you can see just how far these ideas first presented in "Persona" would make their way into their later career. The "movie brats" where all about realism, and Bergman was about as real as you could get.

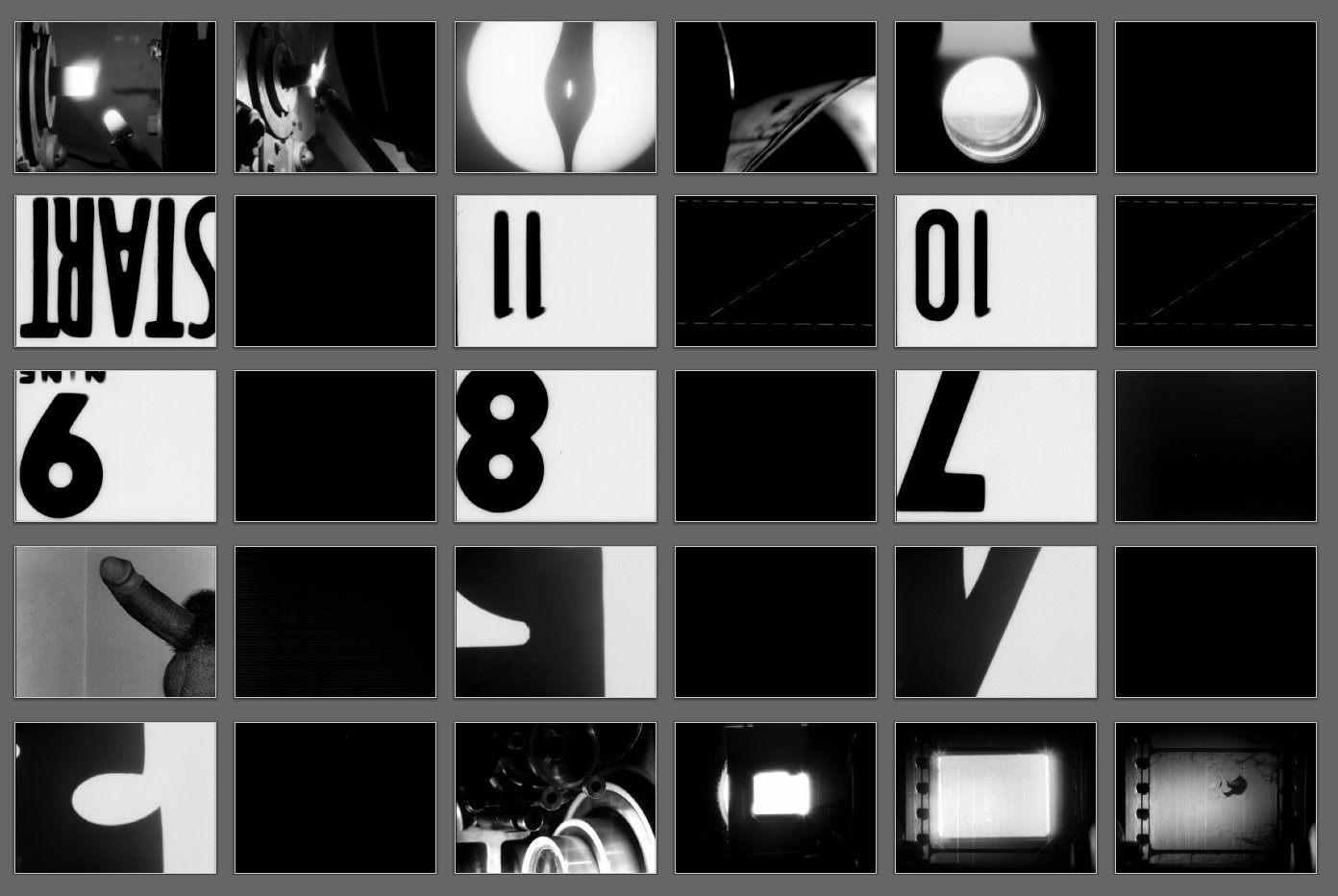

The reason I chose Persona for this blogpost is simply this: I have never seen a movie that was so transparent in its control of the audience as this one. As the film starts, it lets you know that you're watching a movie. You see the projector start to run as various shots shoot across the screen and take you through a series of unrelated stock footage, and a humorous freeze frame of an erect penis. Then the film shows you a bunch of dead people and this monotonous dripping sound in the background. And then it shows you some skinny kid reach out towards a blurry image of a woman. By this point, just about anybody is scratching their heads in confusion. Bergman has just begun his magic trick onto the audience.

At this point, the movie starts to somewhat introduce a dramatic plot about an actress who has gone mute. A nurse is assigned to watch over her and get to know her. She spends a large amount of time telling the mute actress all about her life, and her personal life experiences. She tries to get the actress to talk multiple times, but it simply does not work. They then go in isolation with each-other as part of the actress' treatment. It is here that the film starts to give you an impression that it has eased into a comfortable drama and the illusion of the invisible director starts to take shape. This is dashed, however, when in a climactic moment of the drama, the film literally burns up and stops and shows you some more unrelated stock footage. This is Bergman telling the audience that he still has control of their experience and that the drama they are seeing is a fabrication. It is such a power move and completely unprecedented and one of the all time greatest moments in the entire history of the medium. After that, there are many other appearances of the director, including a very literal appearance where you see the entire crew and camera set up in a mirror reflection. Bergman isn't attempting to create an illusion of immersion, he is desperately forcing you to be aware of how fabricated everything is. This isn't just a deconstruction of the cinematic orthodoxy, this is a film about the art of film itself. It has grown sentience with "Persona". In fact, the persona of "Persona" is film itself. I can't think of anything that can be more auteur than that, than to literally grab your audience by the head and make them understand as plain as day that they are watching a movie that had intelligence behind it, and a crew that made every little moment possible. Nothing is real, it is all just a movie. It took a tremendous amount of gall to be able to do that, but thank God he did because that was also one of the first films to give transparency to the filmmaker which inspired many young filmmakers of the time and gave them the confidence to play around their own sensibilities. Hollywood was never transparent like that. The only indication that there was any director or crew involved at all were the opening credits and they were instantly forgotten by the time the narrative started.

Besides "Persona," Bergman's work was largely identifiable as his own. His auteur trademarks include female interrelationships, religion, pain and torment, mortality, unrequited love and the list goes on and on. He pretty much used the same troupe of Swedish actors for his entire career, and even sparked the careers of many Swedish international stars such as Max von Sydow and Pernilla August, who became famous in 1999 when she portrayed the mother of Anakin Skywalker in "Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace". There was also this island that he filmed most of his films on, and even lived at during the last decades of his life. The island has since been dubbed "Bergman Island" in his honor and there is currently a film being made about it by filmmaker Mia Hansen-Love.

In short, Bergman always had control over his films. In fact, he originally came from the stage and was also a playwright, so his sensibilities automatically fit the auteur style that was originally defined by Truffaut. The revolution was started by Hitchcock with "Vertigo" and "Psycho", and then maintained by French New Wave films like "The 400 Blows" and "Breathless" and then perfected with Bergman's "Persona". And then it hit America with the New Hollywood movement with films such as "The Graduate" and "2001: A Space Odyssey" and is even present in Martin Scorsese's debut "Who's That Knocking at My Door"... and it progressed throughout the 70s, until Michael Cimino's blunder "Heaven's Gate" crashed the film industry in 1980, and pure auteur cinema would be dead until the revival in the mid-1990s with the rise of independent films. There have been several small revolutions in film since then, but they have never been as big or as epic as the auteur revolution. With as young of an art-form that cinema is, it only anyone's guess at what the future will hold. But one thing's for sure, Bergman could have reached the zenith of film history with "Persona", but I guess that will be up for future generations to decide.

Persona analysis by the YouTuber "Renegade Cut"

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a9BWDVhly5Y&t=243s

No comments:

Post a Comment